Once again we are emerging from a period of economic contraction with monetary policy breaking all previous records of just how accommodative central bankers can be. And once again there is a rising chorus of alarm about potential inflation on the horizon. Similar alarm bells were raised following the 2001-2002 bear market and the 2008 financial crisis. They also chimed in 2011 when commodity prices rose sharply, in 2013 during the taper tantrum and in 2016 shortly after Trump was elected. Each time, however, the inflationary wolf failed to materialize.

Questions about inflation have been commonplace during client events we have hosted so far in 2021, so is there reason to be concerned? Will the wolf finally appear? Below we have outlined our thoughts about the near term and some important longer-term trends.

QE – It Is Different This Time

All things being equal, if central banks are actively using their balance sheet to deploy quantitative easing (QE or buying of financial assets), this is inflationary. Of course this leads to the question, why didn’t we see any inflationary result from the QE that was piled on for years after the 2008 financial crisis? The fact is things are rarely equal.

In the years following 2008, QE had a short circuit that limited its impact on the real economy, which is where inflation happens. In the U.S., the Federal Reserve’s purchase of financial assets led to financial institutions building their reserves and capital ratios (or in many cases repairing). They likely would have lent more out into the real economy, increasing the money supply, and causing some inflation pressure, but there wasn’t demand. As a result, QE (2008-2016) resulted in asset-price inflation but really didn’t make a dent in the economy. This also increased income disparity. Meanwhile outside the U.S., QE in Europe and Japan was offset by fiscal restraint or austerity. Again, the result was asset-price inflation but limited economic inflation or growth.

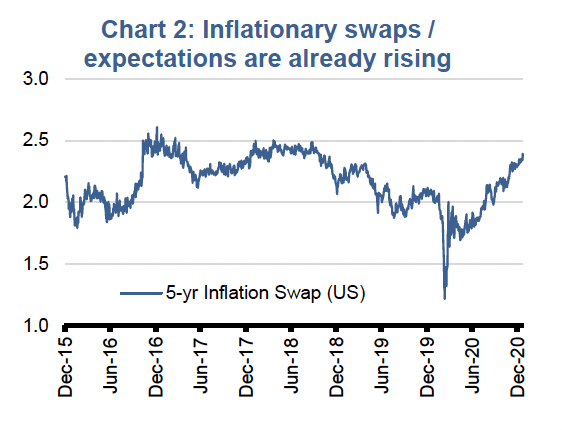

Today QE is different. The financial institution or middleman has somewhat been removed. We currently have central banks buying up trillions in bonds; meanwhile governments have been issuing trillions of bonds to fund fiscal spending programs. As a result, a greater portion of this stimulus has gone directly into the real economy. This would be inflationary, but since we are in a recession, it is just offsetting much of the deflationary pressures. As the economy recovers, and if policy remains very accommodative – as promised by just about every central bank – inflation may actually appear this time. It is already reflected within inflation expectations and bond break-evens (Chart 2).

Short Term – Cyclical Uptick in Inflation

One could easily dismiss any short-term uptick in inflation given the size of the output gap. This is the difference between current economic activity and the economy’s potential. Every major country currently has an output gap as these economies recover amid efforts to counter the pandemic that weighs heavily on a number of industries. This economic slack is deflationary as is 6.7% unemployment in the U.S. and 8.6% in Canada.

However, the current recession and recovery are unique. The high unemployment rate is concentrated within a handful of industries, mainly select services, which are most impacted by socially distancing efforts. Unfortunately, the skill set of the labour pool in these most impacted industries is not conducive to switching into industries with tighter labour markets. As a result, the overall or headline high level of unemployment is not translating into broader downward wage pressures.

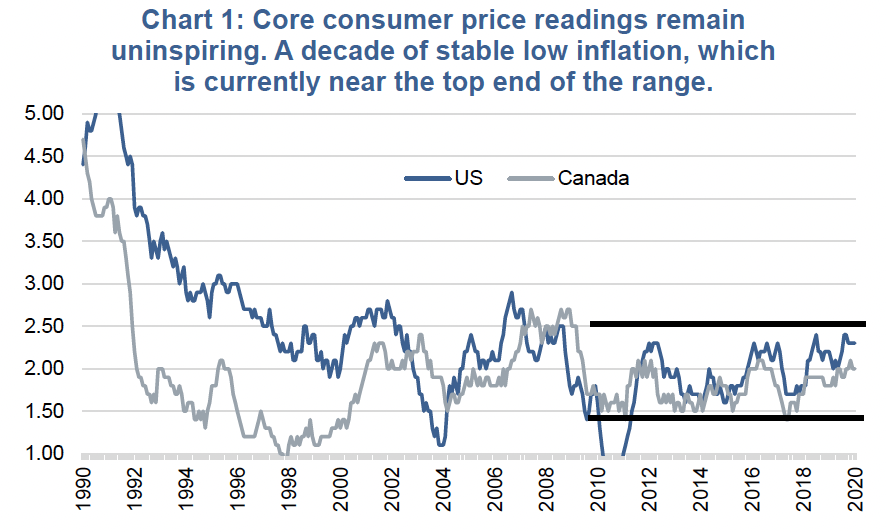

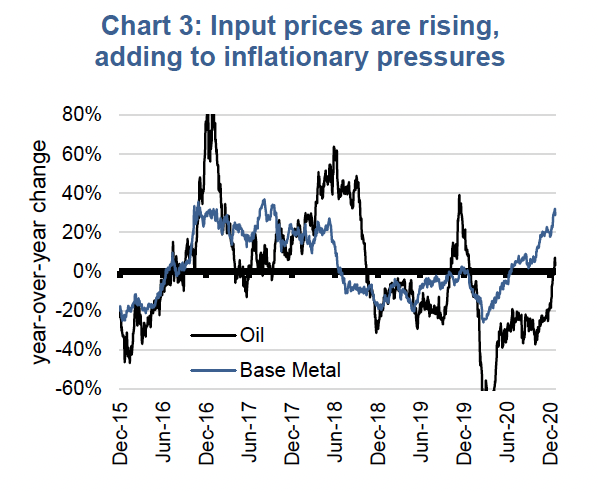

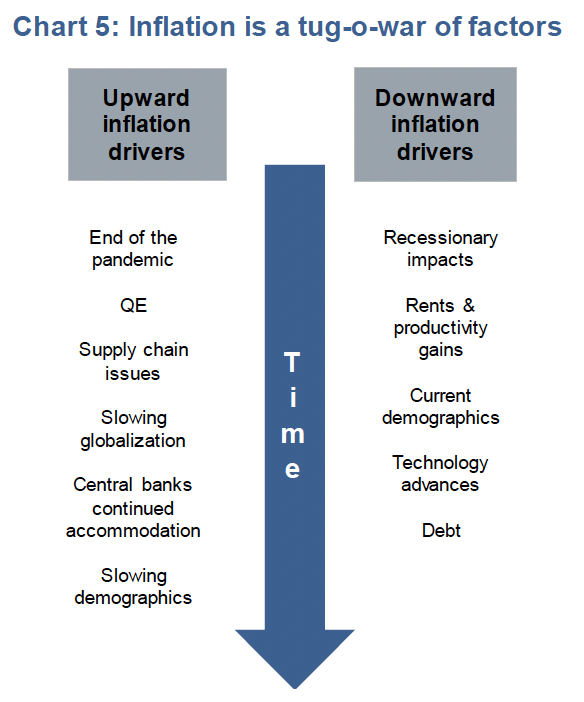

There are also some short-term inflationary impulses that could lift inflation outside of its decade-old range (Chart 1). Supply disruptions due to the pandemic and rising logistics costs are putting upward pressure on many input prices (Chart 3). At the same time, demand continues to gradually recover. These will likely filter down to final prices in time.

Countering this inflationary pressure, rents are declining. Given the weight rent carries in CPI, it would be difficult to see a big rise in near term inflation. Plus, productivity gains thanks to increased use of technology during this pandemic could further hold back near term inflation.

Taken all together, if aggregate demand (global economic recovery) continues to improve or pick up as the vaccine is rolled out, this may accelerate short-term inflationary pressures. And the headline numbers will certainly rise as the data passes the one year mark from when this pandemic began impacting economic data.

Longer Term – A Bigger Trend

Much of the above is dealing with the short-term impact of policy, the pandemic, and the recovery on inflation. And even if there is an uptick, it likely won’t last as these are cyclical drivers. Long-term trends dominate when it comes to prices and inflation. While not an exhaustive list, the big deflationary pressures over the past few decades have been globalization, technology, and demographics.

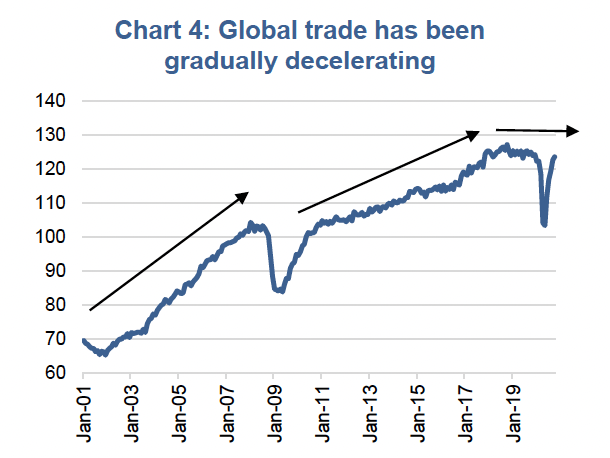

Globalization – Moving a supply chain to a lower-cost jurisdiction enables lower prices. This is clearly deflationary. A case in point: after China entered the World Trade Organization (WTO), global manufacturing was reconfigured with many operations moving to China and other countries. Freer trade and improved logistics enabled global trade to substantially increase. However, it has now slowed down. The simple reason is that much of what can be moved has already been moved (Chart 4).

As the globalization deflationary impulse fades, a renewed initiative to migrate more of the supply chain closer to end markets has started. While it

is difficult to know whether this ‘reshoring’ trend will persist after the pandemic fades, it’s safe to say that the growth in offshoring is likely in its

twilight years.

Technology – This remains deflationary and will likely remain. Anything that enables productivity growth allows a company to maintain profits at a lower price point. Big data, 5G, automation, autonomous vehicles—the list of innovative solutions is a long one and most technologies put downward pressure on prices over time.

Side note: Not all technologies are deflationary. I still fail to see how sharing a picture of me eating something with others improves my productivity, or theirs. But I’m probably just the wrong generation! And speaking of generations…

Demographics – An aging population is deflationary as a larger portion of the population moves from the prime spending phase of their lives to the gradual decumulation phase. The baby boomers entering retirement have been a long-term trend over the past few decades, putting downward pressure on prices.

While this trend isn’t going away, it is gradually entering a less deflationary phase. Millennials are increasingly entering the household-formation phase at the same time the pace of baby boomers retiring slows. Household formation is when you transition from experiential spending to figuring out, for instance, that you need a second vehicle to drive kids to separate sports or other extra-curricular activities on the same day. The second car is inflationary.

Deflationary pressures are not going away soon. But it does appear that many are becoming less deflationary and will continue to do so over the coming years. As this long-term deflationary pressure gradually abates, to a degree, and central banks likely continue to re-imagine the new limits of monetary easing, we believe inflation will trend higher during the 2020s decade.

Investment Implications

If we are entering a period of rising inflation, or you agree there is a higher risk of inflation, there are many investment implications. Many of the successful strategies of the past few decades will struggle. Value stocks tend to win over Growth stocks during periods of rising inflation. Real assets win over paper or financial assets. The 60/40 portfolio will be challenged as will risk parity.

Another challenge is that you have to look back so far to examine an inflationary period, but many of the strategies today simply didn’t exist. Back-testing and historical performance will therefore become less useful. Investors will have to creatively imagine how strategies or products may perform amid any rise in inflation.

Don’t worry just yet though. The initial years of rising inflation historically have been healthy for the

Charts are sourced to Bloomberg L.P. unless otherwise noted.

The contents of this publication were researched, written and produced by Richardson Wealth Limited and are used herein under a non-exclusive license by Echelon Wealth Partners Inc. (“Echelon”) for information purposes only. The statements and statistics contained herein are based on material believed to be reliable but there is no guarantee they are accurate or complete. Particular investments or trading strategies should be evaluated relative to each individual's objectives in consultation with their Echelon representative.

Forward Looking Statements

Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations, estimates, forecasts and projections based on beliefs and assumptions made by author. These statements involve risks and uncertainties and are not guarantees of future performance or results and no assurance can be given that these estimates and expectations will prove to have been correct, and actual outcomes and results may differ materially from what is expressed, implied or projected in such forward-looking statements.

The opinions expressed in this report are the opinions of the author and readers should not assume they reflect the opinions or recommendations of Echelon Wealth Partners Inc. or its affiliates. Assumptions, opinions and estimates constitute the author’s judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. We do not warrant the completeness or accuracy of this material, and it should not be relied upon as such. Before acting on any recommendation, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, if necessary, seek professional advice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. These estimates and expectations involve risks and uncertainties and are not guarantees of future performance or results and no assurance can be given that these estimates and expectations will prove to have been correct, and actual outcomes and results may differ materially from what is expressed, implied or projected in such forward-looking statements.

The particulars contained herein were obtained from sources which we believe are reliable, but are not guaranteed by us and may be incomplete. The information contained has not been approved by and are not those of Echelon Wealth Partners Inc. (“Echelon”), its subsidiaries, affiliates, or divisions including but not limited to Chevron Wealth Preservation Inc. This is not an official publication or research report of Echelon, the author is not an Echelon research analyst and this is not to be used as a solicitation in a jurisdiction where this Echelon representative is not registered.

The opinions expressed in this report are the opinions of its author, Richardson Wealth Limited (“Richardson”), used under a non-exclusive license and readers should not assume they reflect the opinions or recommendations of Echelon Wealth Partners Inc. (“Echelon”) or its affiliates.

This is not an official publication or research report of Echelon, the author is not an Echelon research analyst and this is not to be used as a solicitation in a jurisdiction where this Echelon representative is not registered. The information contained has not been approved by and are not those of Echelon, its subsidiaries, affiliates, or divisions including but not limited to Chevron Wealth Preservation Inc. The particulars contained herein were obtained from sources which we believe are reliable, but are not guaranteed by us and may be incomplete.

Assumptions, opinions and estimates constitute the author’s judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Echelon and Richardson do not warrant the completeness or accuracy of this material, and it should not be relied upon as such. Before acting on any recommendation, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, if necessary, seek professional advice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. These estimates and expectations involve risks and uncertainties and are not guarantees of future performance or results and no assurance can be given that these estimates and expectations will prove to have been correct, and actual outcomes and results may differ materially from what is expressed, implied or projected in such forward-looking statements.

Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations, estimates, forecasts and projections based on beliefs and assumptions made by author. These statements involve risks and uncertainties and are not guarantees of future performance or results and no assurance can be given that these estimates and expectations will prove to have been correct, and actual outcomes and results may differ materially from what is expressed, implied or projected in such forward-looking statements.